Protein

Adequate protein intake is essential to help minimise declines in strength and function.27 High protein supplements can help reduce complications and improve weight.28

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUSCLE STRENGTH THE BURDEN OF MUSCLE LOSS CAUSES OF LOW MUSCLE MASS CONSEQUENCES OF LOW MUSCLE MASS MUSCLE LOSS, SARCOPENIA AND FRAILTY CAN BE REVERSED THE IMPORTANCE OF MALNUTRITION AND MUSCLE SCREENING/ASSESSMENT THE IMPORTANCE OF MEDICAL NUTRITON ABBOTT’S RANGE OF NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS RESOURCES

As our population ages, so too does the demand on our healthcare system.5

The focus for NHS organisations is to deliver a proactive population health approach for patients as they age. This is especially important for those most at risk of negative health outcomes such as frailty/pre-frailty and muscular skeletal-conditions, where early identification and intervention can improve strength, reduce falls and hospital admissions, and help people maintain their independence as they get older.6

Strategies for healthy aging typically focus on optimising health and minimising chronic disease and physical decline, with the ultimate goal of helping individuals maintain their independence.4 However, a notable consequence of ageing is the involuntary decline of muscle mass, strength and function, sometimes referred to as sarcopenia.7

Sarcopenia is defined as an age-related loss of muscle, but loss of muscle mass/function can be seen as early as the age of 30:7,8

Sarcopenia often leads to frailty, a term which typically incorporates a reduction in health, energy levels and cognition, leading to increased susceptibility to further illness and a decline in physical and mental health.1,4

Frailty is a common consequence of ageing and is closely related to sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) due to their shared physical characteristics i.e. lower lean mass and reduced muscular function.9

As adults become less active, and consume less protein and calories due to other chronic diseases, this can lead to fatigue, accelerated sarcopenia and an overall decline in muscle mass.8

Sarcopenia is prevalent in up to 13% of adults aged 60-70 years, increasing to 50% in people aged >80 years.10

Frail patients are at increased risk of malnutrition, muscle loss and worsening frailty due to:11,12

In a stressed state, the body requires more amino acids from muscle breakdown, leading to accelerated protein degradation as amino acids are released to deal to increase metabolic rate for fuel. Patients with low muscle mass have difficulty coping with metabolic stress, negatively impacting survival, and recovery.13

Extended periods of immobilisation, such as during acute hospitalisation, can worsen muscle loss and prolong recovery. If muscle loss persists before the body enters a stressed state, restoring normal function becomes unlikely.13

Sarcopenia and frailty are associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes for patients, particularly as they age:14-16

Increased risk of disability

Reduced quality of life

Poor balance and increased falls

Impaired immune function

Compromised wound healing

Higher risk of mortality

Consequences of frailty on patients' quality of life

Sarcopenia and frailty can also have a significant impact on patients’ daily life, their social and their mental health. Patients with sarcopenia often experience a significant physical burden which can result in the inability to perform simple daily tasks, such as standing and walking and often suffer with fatigue, muscle pain and falls.17

Moreover, patients often report that their sedentary lifestyles actually make these issues worse. In addition to the physical limitations that sarcopenia poses, patients have also described the emotional impacts of feeling physically frail such as embarrassment of their physical limitations and feeling isolated due to limiting social interactions.17

Although frailty and declining physical function are associated with increased age, promoting healthy ageing from middle age onwards could delay the onset of frailty as people grow older.4 There is also evidence that improving nutrition and weight loss can reduce frailty.9

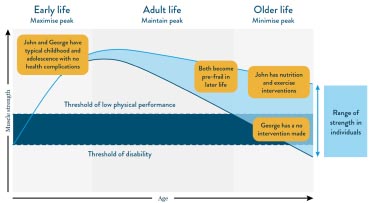

Muscle strength over a lifetime15

Figure above adapted from Cruz-Jentoft, 20191.

John and George are not based on actual patient case studies and are for example purposes only.

Timely identification of frailty symptoms, such as loss of muscle mass, combined with targeted support, including nutritional intervention, can improve patients’ quality of life, enabling them to live independently for longer.18-20

Frailty can be costly to healthcare services, with social care costs calculated to be over 800% higher for frail people than non-frail people. However, for every 1% of people in England prevented from developing frailty, social care savings of £4.4m per annum could be realised.21,22

Screening for undernutrition/frailty is critical for early assessment and intervention to maintain functionality and support healthy ageing.23

Muscle screening and assessment are recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2).24 They can be quick, inexpensive and easy to apply in clinical practice.24,25

Screening can easily identify limited strength and performance, a strong predictor of adverse negative health outcomes and can be easily used to increase physical activity and implement nutrition interventions.25,26

To prevent the decline in muscle strength in older life, early interventions should be made with nutrition and exercise.15

Key Nutrients Can Increase Muscle Strength and Improve Quality of Life

Adequate protein intake is essential to help minimise declines in strength and function.27 High protein supplements can help reduce complications and improve weight.28

HMB is a metabolite of leucine, a branched-chain essential amino acid exclusively obtained from dietary sources29

Vitamin D acts directly on muscle to promote its function through specific vitamin D receptors found on muscle cells.30 It plays an important role in maintaining musculoskeletal health and can help reduce the risk of falls and improve mobility.32,33

Ensure Plus Advance§ is a 220ml, ready to drink ONS. It contains a unique blend of protein, vitamin D and HMB that improves strength and reduces the risk of mortality in various patient populations.*,†,‡‡,§§,¶,¶¶,~,#,34-41 It is the high protein, high energy ONS people prefer to drink vs. a high protein compact**,††,42,43 and achieves 96% compliance.^,39

Validated by more than 18 clinical studies34-41,44-58, Ensure Plus Advance is proven to significantly increase strength and improve the quality of life in various patient populations.*,†,‡‡,§§,¶,¶¶,~,##,34-41

The unique blend of protein, vitamin D and HMB in Ensure Plus Advance has been shown to significantly improve outcomes for patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture:§§§,37

A range of nutritional supplements designed to meet the different needs of patients with frailty.

Ensure Plus juce

Ensure Plus juce is a 1.5 kcal/ml, ready-to-drink, juice style oral nutritional supplement for people with, or at risk of developing, disease-related malnutrition. Ensure Plus juce is best served chilled and is available in six flavours: apple, fruit punch, lemon and lime, orange, peach and strawberry. It's presented in a 220 ml bottle with a peel-off seal for pouring.

Ensure Compact

Ensure Compact is a 125 ml, ready-to-drink, nutritionally complete§ oral nutritional supplement for people with, or at risk of developing, disease-related malnutrition. Its small volume has been specially developed for people who have difficulty drinking larger volumes or who have a poor appetite. Each easy-to-open Ensure Compact bottle1 provides 300 kcal (2.4 kcal/ml) and 12.8 g of protein.

Ensure Compact is available in 4 delicious flavours; banana, café latte, strawberry and vanilla.

§Nutritionally complete for vitamins and minerals in 625 ml (excluding sodium, potassium, chloride and magnesium). Calculated using the UK Reference Nutrient Intake for men aged 19-50 years.

Vital 1.5kcal

Vital 1.5kcal is suitable for people with disease-related malnutrition and malabsorption or for those who experience symptoms of poor feed tolerance. Vital 1.5kcal is peptide-based* and available both as a 200 ml oral nutritional supplement, and as a 1000 ml Ready to Hang tube feed, both of which attach directly to Abbott giving sets. Oral nutritional supplement flavour options include: café latte, mixed berry and vanilla.

*Peptides are partially broken down proteins, which makes them easier to digest and absorb in the gut than whole proteins.

On-demand webinar — Assessing muscle mass and function: practical tools and nutritional interventions to improve patient outcomes

In this UK webinar, Ione De Brito-Ashurst discusses the importance of muscle mass for improving clinical and financial outcomes.

Video — Understanding the impact of sarcopenia in frailty: going from strength to strength

In this 22-minute video, Dr Sanjay Suman, discusses the new definition of sarcopenia, and its relationship with osteoporosis and risk of falls due to poor muscle strength. Dr Suman explains how to manage sarcopenia through nutrition and exercise.

UK-N/A-2300362 | October 2023

Footnotes

§ ACBS indication: as a nutritional supplement for frail elderly people (>65 years of age, with a BMI ≤ 23kg/m2), where clinical assessment and nutritional screening show the individual to be at risk of undernutrition. * As shown in a randomised control trial to investigate the effects of the intervention ONS on malnourished, cardiopulmonary patients (≥65 years) vs placebo. The intervention ONS decreased mortality at 90 days post-discharge, however the study did not observe a significant effect for the primary composite endpoint of non-elective readmission or death. This post-hoc, sub-group analysis from the NOURISH study cohort comprised 214 COPD patients. †Strength was measured by handgrip strength in a post hoc analysis of over 600 malnourished people with heart or lung diseases, age 65 or older. Study product was consumed twice a day for 30 days, as compared to standard of care. ‡‡ In 330 older adults with malnutrition and sarcopenia. Muscle quality was calculated as leg strength expressed relative to the muscle mass. §§ As shown in a randomised control trial to investigate the effects of a specialised ONS on older women (≥65 years) who underwent surgery for hip fracture vs. standard post-operative nutrition. Post-operative nutrition provided 1900 kcal and 76 g protein a day. Muscle function was measured by handgrip strength. Mobilisation status was assessed on post-operative days 15 and 30. ¶ An open-label study of elderly (n=35) patients with recent weight loss (>5% during previous 3 months) showed that 12 weeks supplementation of experimental product twice daily increased dietary intake, biochemical variables, and quality of life compared to baseline. ¶¶ In 65 healthy older female patients who regularly attended a fitness programme. ~ As shown in a randomised controlled trial in which normally nourished patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis received pulmonary rehabilitation plus a specialised ONS or pulmonary rehabilitation only for 12 weeks. In the intervention group, mean and maximum handgrip dynamometry, physical functioning domain of QOL-B-V3.0 and other outcomes were significantly increased from baseline at 12 weeks and 24 weeks and fat free mass at 12 weeks. # As shown in a randomised control trial to investigate the effects of the intervention ONS on malnourished, cardiopulmonary patients (≥65 years) vs placebo. The intervention ONS decreased mortality at 90 days post-discharge, however the study did not observe a significant effect for the primary composite endpoint of non-elective readmission or death. ** Vs. market-leading high protein compact. ††243 healthy adults who were asked to drink comparative flavours of Ensure Plus Advance and Fortisip Compact Protein. ^ Research with 80 healthy women over 65 years of age supplemented with one serving of Ensure Plus Advance daily for 8 weeks. ##In a single arm open-label study of 148 patients aged 80±8.3 years with or at risk of malnutrition who consumed experimental product twice daily for 12 weeks as compared to baseline. §§§As shown in a randomised control trial to investigate the effects of a specialised oral nutritional supplement (ONS) on older women (≥65 years) who underwent surgery for hip fracture vs standard postoperative nutrition. Mobilisation status was assessed on postoperative days 15 and 30. The control group received standard postoperative nutrition (1900 kcal and 76 g protein a day), while the intervention group received 2 servings a day of a high protein ONS with calcium ß-hydroxy-ß·methylbutyrate and additional vitamin D between meals in addition to the standard postoperative nutrition plan. Muscle function was measured by handgrip strength.

References

1. Xue QL. Clin Geriat Med 2011;27(1):1–15. 2. Mühlberg W. & Sieber C. Gerontol Geriat 2004;37:2–8. 3. Takatori K. & Matsumoto D. PLOS ONE 2021;16(3):e0247296. 4. Gordon SJ. et al. BCM Geriatrics 2020;20:96. 5. Walsh B. et al. Age and Ageing 2023;52:1-9. 6. NHS 2019. The NHS Long Term Plan. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf Last accessed November 2023. 7. Volpi E. et al. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004;7(4):405-410. 8. Waltson JD. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012;24(6):623-627. 9. Roberts S. et al. Nutrients 2021;13(7):2316. 10. von Haehling S. et al. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010;1(2):129-133. 11. Padilha de Lima A. et al. J Nutr Health Aging 2022;26:67-76. 12. Álvarez Satta M. et al. Ageing 2020;12(10):9982-9999. 13. Wolfe RR. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:475-82. 14. Argiles JM. et al. JAMDA 2016;17:789-796. 15. Cruz-Jentoft AJ. et al. Age and Ageing 2019;48:16-31. 16. Demling RH. Eplasty 2009;9:e9. 17. FDA 2017. The Voice of the Patient. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/The-Voice-of-the-Patient--Sarcopenia.pdf Last accessed October 2023. 18. Ackermans L. et al. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2022;48:36-44. 19. Wilson D. et al. Ageing Res Rev 2017;36:1-10. 20. NHS, 2022. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical policy/older people/frailty/efi/. Last accessed 22nd November 2022. 21. Álvarez Bustos A. et al. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:747. 22. Nikolova S. et al. Health Soc Care Community 2022;30:e804. 23. Jaime J. et al. Advances in Nutrition 2021;12(6):2312-2320. 24. Cruz-Jentoft AJ. et al. Age Ageing 2010;39:412-23. 25. Beaudart C. et al. Calcif Tissue Int 2019;105,1-14. 26. Murayama I. et al. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:913-920. 27. Deutz NE. et al. Clin Nutr 2014;33(6):929-936. 28. Cawood AL. et al. Ageing Res Rev 2012;11(2):278-296. 29. Wilson GJ. et al. Nutr Metab 2008;5:1. 30. Wagatsuma A. and Sakuma K. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:121-254. 31. European Food Safety Authority. EFSA J 2010;8(2):1468. 32. European Food Safety Authority. EFSA J 2011;9(9):2382. 33. Zhu K et al. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(11):2063-2068. 34. Deutz NE. et al. Clin Nutr 2021;40(3):1388-1395. 35. Matheson EM. et al. Clin Nutr 2021;40(3):844-849. 36. Cramer JT. et al. JAMDA 2016;17(11):1044-1055. 37. Ekinci O. et al. Nutr Clin Pract 2016;31(6):829-835. 38. De Luis DA. et al. Nutr Hosp 2015;32(1):202-207. 39. Berton L. et al. PLoS one 2015;10(11):e0141757. 40. Olveira G. et al. Clin Nutr 2016;35(5):1015-1022. 41. Deutz NE et al. Clin Nutr 2016;35(1):18–26. 42. Data on file. Abbott Laboratories Ltd, 2023 (Ensure Plus Advance acceptability and compliance vs Fortisip Compact Protein). 43. IMS Data, July 2023. 44. Ashkenazi I. et al. Geriatr Orhop Surg Rehabil 2022;13:21514593221102252. 45. Chavarro-Carvajal DA. et al. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2022;48:291-297. 46. Cornejo-Pareja I. et al. Nutrients 2021;13(12):4355. 47. De Luis DA. et al. Eur Geriatr Med 2018;9(6):809-817. 48. Espina S. et al. Nutrients 2021;13(11):3764. 49. Lopez-Rodriguez-Arias F et al. Support Care Cancer 2021;29(12):7785-7791. 50. Malafarina V. et al. Maturitas 2017;101:42-50. 51. Peng LN. et al. J Nutr Health Aging 2021;25(6):767-773. 52. Previtali P. et al. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27(6):2025-2032. 53. Ritch CR. et al. J Urol 2019;201(3):470–477. 54. Standley RA. et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020;75(9):1744-1753. 55. Zana S. et al. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22(7):1358-1360.

You are about to exit for another Abbott country or region specific website.

Please be aware that the website you have requested is intended for the residents of a particular country or region, as noted on that site. As a result, the site may contain information on pharmaceuticals, medical devices and other products or uses of those products that are not approved in other countries or regions.

The website you have requested also may not be optimised for your specific screen size.

Do you wish to continue and exit this website?

UK-N/A-2200465 | July 2022

UK-N/A-2200443 | June 2022

Stay Connected